Cassava leaves stand out for their surprising benefits, everyday uses in cooking, agriculture, and traditional practices across diverse cultures, offering more than you think.

You may recognize cassava for its starchy and tuberous roots, but the leaves deserve just as much attention.

The cassava leaf is commonly used in African, Asian, and South American cuisines, as it holds nutritional and medicinal value that many overlook.

When properly prepared, they serve as a rich source of protein, fiber, and vital micronutrients like iron, calcium, and vitamin C.

In this guide, you’ll gain a closer look at what makes cassava leaves so valuable, from their detailed anatomy to the nutrients packed into every portion.

You’ll also learn how traditional communities cook and consume them, and why their health benefits are worth your attention.

If you are new to cassava, the super crop, start here.

What is the Cassava Leaf?

Cassava leaves are the green parts of the cassava plant that you can eat once they’re properly cooked.

You’ll recognize them by their hand-like shape with long, narrow lobes that spread from the center.

In many African and Southeast Asian kitchens, these leaves are a regular part of meals.

They bring real value to your plate: protein, fiber, iron, and vitamins A and C. But here’s something important: you can’t eat them raw.

They contain compounds that turn into cyanide if not boiled long enough.

Cook them well, and you get a safe, hearty ingredient with a strong presence in both food and traditional healing.

Cassava leaves also matter in farming and trade, especially in areas where fresh greens aren’t easy to come by. New to cassava? Here is a comprehensive post on the cassava plant.

Botanical Profile

This section looks at the plant’s scientific background, what the leaves look like, and the different types commonly used for food.

Understanding these basics helps you know exactly what you’re cooking or eating.

Scientific Name and Classification

Cassava belongs to the species Manihot esculenta and is part of the Euphorbiaceae family.

Botanically, it’s classified as a perennial shrub with thick stems, latex-filled parts, and deeply lobed leaves.

Its structure and growth habits are similar to other plants in its plant family, like castor and poinsettia.

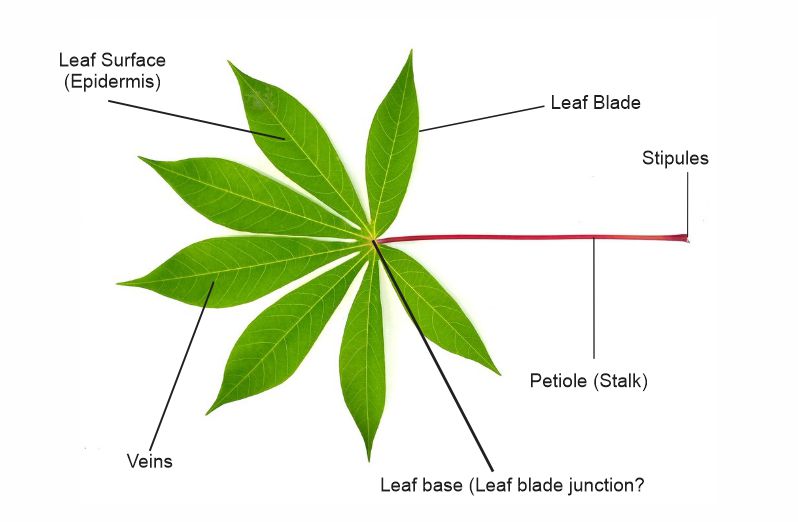

Description of Cassava Leaves: Including All the Parts and Functions

Cassava leaves are compound leaves made up of multiple lobes that radiate from a central point, giving them a palm-like appearance.

They are typically green, broad, and soft-textured when young, becoming tougher as they mature.

Each leaf has distinct parts with specific roles that contribute to the plant’s overall function.

Leaf Blade (Lamina)

The leaf blade is the broad, flat portion of the cassava leaf. It is divided into lobes, usually between 5 and 9, that increase the surface area for photosynthesis.

This is the main site where the plant converts sunlight into energy.

Petiole

The petiole is the long, slender stalk that connects the leaf blade to the main stem.

It supports the leaf and transports water, nutrients, and photosynthetic products between the leaf and the rest of the plant.

Petioles are typically red, purple, or green, depending on the cassava variety.

Stipules

Stipules are small, leaf-like structures found at the base of the petiole.

Though not always prominent, they serve as protective structures for the growing leaf and may fall off as the leaf matures.

Veins

The veins run through each lobe of the leaf and consist of a central midrib with branching veins.

They form the transport network within the leaf, carrying water to the cells and distributing sugars produced during photosynthesis.

Leaf Surface (Epidermis)

The epidermis is the outer layer of the leaf. It contains microscopic pores called stomata, which regulate gas exchange and water vapor loss.

The upper surface often has a waxy coating to reduce water loss, especially in dry conditions.

Functions of Cassava Leaves

- Photosynthesis: The main role of the cassava leaf is to capture sunlight and convert it into chemical energy that fuels the growth of the plant.

- Transpiration: Through stomata, the leaf regulates water movement and internal temperature, helping with nutrient uptake from the roots.

- Nutrient Storage: They are rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals. Though they must be properly cooked to remove toxins, they are nutritionally valuable in many diets.

- Growth Regulation: The leaves play a role in hormone signaling and overall plant development by producing compounds that influence root and shoot growth.

The White Sap in Cassava Leaves

The sap in cassava leaves contains cyanogenic glycosides, primarily linamarin and lotaustralin.

These natural plant compounds can release hydrogen cyanide (HCN) when the plant tissue is damaged, such as during chewing, pounding, or juicing.

The release occurs through enzymatic activity that converts the glycosides into cyanide, which is toxic to humans if consumed in significant amounts or without proper detoxification.

In addition to cyanogenic glycosides, cassava leaf sap may also contain small amounts of proteins, chlorophyll, enzymes, and plant acids, but the primary health concern is the potential for cyanide poisoning.

This is why proper preparation, including soaking, boiling, or fermenting the leaves, is crucial before any consumption of cassava leaf products.

Recommended: 11 Benefits of Cassava Leaves

Anatomy of the Cassava Leaf

The internal anatomy of a cassava leaf consists of three main tissue layers: epidermis, mesophyll, and vascular tissue.

The upper and lower epidermis form the protective outer layers, with stomata mostly on the lower surface to regulate gas exchange.

Beneath the epidermis lies the mesophyll, which is divided into two parts: the palisade mesophyll, which is densely packed with chloroplasts for photosynthesis, and the spongy mesophyll, with air spaces for gas circulation.

Running through the leaf are vascular bundles, made up of xylem that transports water and minerals, and phloem that transports sugars and nutrients.

This structure supports photosynthesis, respiration, and nutrient distribution, functions essential to the cassava plant’s growth and survival.

Related Posts

How to Make Cassava Leaves Stew

The Many Benefits of the Cassava Plant

How to Handle Frozen Cassava Leaves

How to Cook Cassava Leaves Soup the Traditional Way

Types or Varieties of Cassava Leaves: Bitter and Sweet

The leaves of cassava, like the roots, are classified into two main types based on their cyanogenic glucoside content: bitter and sweet.

This classification influences how the leaves are processed and consumed, as both types contain naturally occurring compounds that can release toxic hydrogen cyanide if not properly prepared.

Bitter Cassava Leaves

Bitter cassava leaves are known for their distinct taste and chemical makeup. Below are the key characteristics that set them apart from their sweet counterparts:

Characteristics

- Contain a significantly higher concentration of cyanogenic compounds, especially linamarin, which can release toxic cyanide if not properly processed.

- Usually come from bitter-root cassava varieties, which are more robust and starch-rich but require careful handling.

- Have a sharper, more pungent taste when raw, making them less palatable without thorough cooking or fermentation.

- Often appear slightly thicker and darker in color than sweet cassava leaves, reflecting their stronger chemical profile.

Functions and Uses

- Require thorough cooking, soaking, pounding, or fermentation to reduce toxicity.

- Commonly used in traditional dishes across Africa and parts of Asia after proper detoxification.

- Preferred for cooking in some cultures due to their strong flavor and ability to withstand longer cooking times.

Sweet Cassava Leaves

Sweet cassava leaves are more palatable and safer to prepare than bitter varieties.

Here are their defining traits and how they’re commonly used in cooking:

Characteristics

- Contain lower levels of cyanogenic compounds, making them comparatively less toxic than bitter cassava leaves.

- Typically come from sweet-root cassava varieties, which are more commonly grown for direct consumption.

- Milder in taste and less toxic, though still unsafe to eat raw due to residual cyanide content.

- Leaves are often more tender and lighter green in appearance, indicating their gentler chemical profile.

Functions and Uses

- Easier to prepare and require less processing than bitter types, making them more user-friendly.

- Still must be cooked, but shorter cooking times are usually sufficient to neutralize toxins.

- Often chosen for soups, stews, and leafy vegetable dishes where a softer texture and milder flavor are preferred.

Risks and Safety Concerns

The leaves of cassava offer nutritional benefits but also come with potential health risks if not properly prepared.

The raw leaves contain toxic compounds that can pose serious safety concerns.

Understanding these risks is essential for ensuring safe consumption and preventing health complications.

Cyanogenic Compounds in Raw Cassava Leaves

The raw leaves of cassava naturally contain cyanogenic glycosides, which release toxic hydrogen cyanide when broken down.

Without proper preparation, consuming these leaves can expose individuals to harmful levels of cyanide.

This makes understanding and mitigating the presence of cyanogenic compounds a critical part of cassava leaf consumption.

Exposure to cyanide from improperly prepared cassava leaves can cause symptoms such as dizziness, nausea, headache, vomiting, and in severe cases, respiratory failure or death.

These symptoms often appear quickly and require immediate medical attention, highlighting the importance of cautious consumption and proper leaf processing.

Importance of Proper Preparation and Detoxification

To reduce toxicity, the leaves must be thoroughly soaked, boiled, or fermented.

These detoxification methods break down cyanogenic compounds, making the leaves safe for consumption.

Proper preparation is not just recommended, it is essential to prevent poisoning and safeguard health, especially in regions where cassava is a staple food.

Safe Consumption Guidelines

Always ensure the leaves are fully cooked before eating.

Avoid eating them raw or undercooked, and follow traditional preparation methods that have been shown to reduce cyanide levels.

Pregnant women, children, and individuals with compromised health should be especially cautious and seek guidance before consuming cassava leaves.

Nutritional Profile of Cassava Leaves

Cassava leaves are a highly nutritious, plant-based food source that deserves a place alongside more commonly praised greens like spinach and kale.

Rich in protein, fiber, and essential micronutrients such as vitamins A, C, and B-complex, as well as minerals like calcium, iron, and potassium, they offer a comprehensive nutritional profile with added antioxidant benefits.

While cooking reduces some nutrient levels, the leaves still retain significant value.

Their high protein content makes them especially appealing for plant-based diets, and their versatility allows them to enhance both traditional and modern dishes.

For those looking to diversify their intake of leafy greens, cassava leaves are not only a flavorful alternative but also a powerful ally in supporting overall health and well-being.

See a dedicated post for the nutritional profile of cassava leaves.

Health Benefits of Cassava Leaves

Cassava leaves are a nutrient-dense, healing food with benefits that go far beyond the plate.

Packed with vitamins A and C, they help boost immune function and support clear, healthy vision.

Their rich fiber content promotes good digestion, encourages regular bowel movements, and nurtures gut health.

As a natural source of plant-based protein, they’re especially valuable for those following vegetarian or low-meat diets.

These leafy greens are also loaded with antioxidants and anti-inflammatory compounds, which may help protect against chronic illnesses, improve skin elasticity, and reduce signs of aging.

Traditional medicine has long used cassava leaves to treat ailments like wounds and fevers, pointing to their enduring value.

Whether you’re looking to strengthen your immunity or diversify your meals, manioc leaves are a smart, nourishing choice.

For a detailed, in-depth look, see our post on Health Benefits of Cassava Leaves.

Culinary Uses of Cassava Leaves Around the World

Cassava leaves are ingredients utilized in various cuisines around the world, each region incorporating them into unique and culturally significant dishes.

Africa

In Africa, manioc leaves are a staple in many countries, particularly in regions where they are readily available and form an integral part of the diet.

One notable dish is Saka Saka, a traditional Congolese dish made by boiling and pounding manioc leaves with ingredients such as palm oil, peanuts, and spices.

This dish is not only a source of nutrition but also a symbol of cultural heritage and a staple of communal gatherings.

Similarly, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Pondu is a beloved dish that features the leaves of cassava.

Pondu involves simmering cassava leaves with onions, tomato, and fish, resulting in a richly flavored and nutritious meal.

The cultural significance of Pondu extends beyond its culinary appeal; it is often prepared for special occasions and communal feasts, underscoring the communal bonds within Congolese society. See a dedicated post on pondu, the Congolese food.

Asia

In Asia, particularly in the Philippines, the leaves are used in a dish called Laing.

Laing is a traditional Filipino dish that involves cooking dried taro leaves, or those of cassava, as a substitute for coconut milk with chili, garlic, and shrimp paste.

The result is a creamy, spicy, and aromatic dish that showcases the rich culinary traditions of the Philippines.

Laing is often enjoyed with steamed rice and is a testament to Filipino ingenuity in using local ingredients to create flavorful dishes.

South America

In South America, the leaves of cassava are incorporated into various traditional dishes, including the renowned Brazilian Feijoada.

Feijoada is a hearty black bean stew that often includes yuca leaves along with pork, sausage, and other ingredients.

This dish is a culinary emblem of Brazilian culture, traditionally served during gatherings and celebrations.

The inclusion of cassava green leaves not only enhances the nutritional value of Feijoada but also adds a distinctive flavor that complements the richness of the stew.

How to Prepare Cassava Leaves Safely

Using cassava green leaves for food is not popular in my cassava farming region, but it is not uncommon to see people who eat them.

One of the major concerns is the white sap in cassava leaves, which contains cyanogenic glycosides, primarily linamarin and lotaustralin, as described earlier, which must be neutralized before eating.

To prepare the leaves safely, traditional methods like boiling, pounding, and fermentation are commonly used to reduce their cyanide content.

In African cuisines, especially in countries like Congo and Sierra Leone, the leaves are pounded into a paste and then simmered for several hours, often with spices and palm oil.

Southeast Asian practices involve repeated boiling and discarding the water to eliminate toxins.

These cooking methods are both cultural and practical, as they significantly reduce the harmful cyanogenic compounds.

It’s important to never consume the leaves raw.

Extended boiling, ideally for at least 30 to 60 minutes, helps ensure the breakdown of cyanide-producing compounds.

Proper preparation is essential to make cassava leaves both safe and delicious for consumption. See an in-depth post on how to cook cassava leaves.

Cassava Leaves in Traditional Medicine

Cassava leaves have long been used in traditional medicine across various cultures.

They’re believed to offer therapeutic benefits, but their use also comes with caution due to potential toxicity.

Folk Remedies and Applications

In traditional medicine, cassava leaves are used to treat ailments like wounds, fever, and digestive issues.

They’re applied topically as poultices or consumed as herbal teas.

These practices are rooted in generations of folk wisdom, especially in African and Southeast Asian communities, where cassava leaves are a common home remedy.

Anti-Malaria Claims and Scientific Backing

Some traditional healers use cassava leaf extracts as a remedy for malaria, citing fever-reducing and anti-parasitic effects.

While anecdotal evidence is strong, scientific studies remain limited.

Preliminary research suggests potential anti-malarial properties, but more rigorous clinical trials are needed to confirm the efficacy and safety of cassava-based treatments.

Cautions with Medicinal Use

Despite their medicinal potential, cassava leaves contain toxic cyanogenic compounds.

Using them medicinally without proper detoxification can lead to poisoning.

Self-treatment with raw or improperly prepared leaves is risky, especially for vulnerable populations.

Always consult a qualified healthcare provider before using cassava leaves for any therapeutic or medicinal purpose.

Farming and Harvesting Cassava Leaves

The cultivation of cassava for its leaves requires careful attention to growing conditions, harvesting techniques, and storage practices.

When done properly, it ensures a safe, nutritious, and sustainable food source from cassava plants.

Ideal Growing Conditions

Cassava plants thrive in warm, tropical climates with well-drained soil and full sunlight.

For healthy cassava leaf production, farmers should maintain moderate rainfall and avoid waterlogged areas.

Regular pruning encourages leaf regrowth, improving both quality and yield.

Proper soil fertility and pest control also contribute to the successful cultivation of edible cassava greens used in many traditional diets.

When and How to Harvest Cassava Leaves

Cassava leaves can be harvested two to three months after planting, once the plant has matured enough to support frequent picking.

Harvesting is typically done by hand, selecting young, tender leaves for optimal taste and lower toxicity.

Sustainable harvesting methods involve removing a few leaves at a time to allow continued growth and avoid stressing the cassava crop.

Storage and Preservation (Fresh, Dried, or Frozen)

Fresh cassava leaves spoil quickly, so proper preservation is essential.

They can be dried in the shade to retain nutrients or blanched and frozen for longer shelf life.

In some regions, fermented cassava leaves are also stored as a traditional method.

Each storage method helps maintain the safety and usability of these nutritious leafy vegetables.

Economic and Cultural Importance

Cassava leaves are more than just a dietary staple; they play a significant role in local economies and cultural traditions.

Their impact spans food security, livelihoods, and international commerce.

Role in Food Security

Cassava leaves are a vital source of nutrition in many developing regions, particularly during food shortages or seasonal gaps.

Rich in protein, vitamins, and minerals, they complement starchy cassava roots and help ensure dietary diversity.

Their adaptability to poor soils and drought conditions makes cassava cultivation crucial for food resilience in rural communities facing agricultural challenges.

Women’s Involvement in Cassava Leaf Processing

Women play a central role in the processing, especially in African countries where the leaves are cooked, dried, or fermented for market and household use.

This labor-intensive activity not only contributes to family nutrition but also offers income-generating opportunities.

Empowering women through training and access to markets enhances food security and local economies.

Local and International Trade

These leaves are increasingly entering local and international markets as demand grows for ethnic and traditional foods.

In urban areas and diaspora communities, frozen or dried leaves are sold in grocery stores and specialty markets.

Their trade contributes to rural incomes, agricultural development, and cultural preservation across borders.

Cassava Leaves vs. Other Edible Leaves

Cassava leaves are often compared to other leafy greens for their taste, texture, and nutrition.

Being familiar with these differences can help you choose the best greens for your meals and health goals.

Comparison with Spinach, Kale, Moringa, and Amaranth

Unlike spinach and kale, the leaves of cassava must be cooked thoroughly to eliminate toxic compounds.

Moringa and amaranth are also popular for their nutrient density, but cassava stands out for its high protein and iron content.

While moringa is often consumed raw or dried as a supplement, cassava greens are used as a hearty vegetable in soups and stews, especially in African and Southeast Asian cuisines.

Taste, Texture, and Cooking Time

Cassava leaves have a robust, slightly bitter flavor and a fibrous texture that softens with long cooking.

They take longer to cook than spinach or kale, often an hour or more, to ensure safety and tenderness.

Nutritionally, as explained in the earlier section, the leaves of cassava offer notable amounts of protein, iron, calcium, and vitamins A and C, making them a powerful addition to the diet when prepared correctly.

Environmental Impact of Cassava Leaves

The cultivation of cassava leaves offers significant environmental benefits, particularly in the area of soil conservation and biodiversity support.

It contributes to the organic matter in the soil, enhancing its nutrient content and overall health.

Biodiversity is another area where cassava foliage has a positive impact.

Cassava fields, often intercropped with other plants, create a diverse agricultural ecosystem.

This diversity not only encourages a variety of flora and fauna but also promotes pest control and reduces the need for chemical pesticides.

As a result, integrating the leaves of cassava into farming practices aligns with sustainable agricultural principles, promoting ecological balance and reducing environmental footprints.

Conclusion

The leaves of cassava hold significant potential in global food systems, particularly for addressing nutritional deficiencies and enhancing food security.

Rich in protein, vitamins A and C, and minerals like iron and calcium, they can combat malnutrition as awareness of their nutritional value increases.

Ongoing research aims to improve the palatability and digestibility of the leaves, historically underutilized due to cyanogenic compounds.

Advances in processing methods, such as fermentation and drying, are vital for making them safe for consumption.

Additionally, developing cassava leaf-based products like powders and ready-to-eat meals can enhance accessibility and appeal.

Their cultivation requires minimal inputs, supporting smallholder farmers and contributing to resilient local food systems.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are cassava leaves good for?

The leaves of cassava are rich in nutrients, providing essential vitamins and minerals. They support digestion, boost immunity, and can help combat malnutrition in vulnerable populations.

Is it safe to eat raw cassava leaves?

No, raw yuca leaves are not safe to eat due to cyanogenic glycosides, which can release cyanide. Proper cooking or blanching is necessary for safety.

What is the other name for cassava leaves?

They are also known as manioc leaves or yuca leaves. They are commonly used in various traditional dishes across different cultures.

Do cassava leaves lower blood pressure?

Manioc leaves contain potassium, which may help regulate blood pressure. However, more research is needed to confirm their effectiveness in lowering blood pressure specifically.

How long should you boil cassava leaves?

It should be boiled for at least 30 to 60 minutes. Prolonged boiling helps break down cyanide compounds and makes the leaves safe to eat.

Are cassava leaves good for weight loss?

Yes, it is low in calories and rich in fiber and protein, making it a nutritious option for weight management when cooked properly.

What do cassava leaves taste like?

They have an earthy, mildly bitter flavor with a slightly grassy undertone. Their taste deepens when cooked, especially with spices or palm oil.

Citations

- https://www.bbc.com/pidgin/articles/ce5rpvd46j0o

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9315608/

Chimeremeze Emeh is a writer and researcher passionate about Africa’s most transformative root crop—cassava. Through his work at cassavavaluechain.com, he explores the entire cassava industry, from cultivation and processing to its diverse applications in food, health, and industrial use.

He also writes for palmoilpalm.com, where he shares his extensive experience and deep-rooted knowledge of palm oil, covering red palm oil, palm kernel oil, and refined products. His work there reflects his lifelong connection to agriculture and his commitment to promoting sustainable value chains in Africa.

Driven by curiosity and purpose, Chimeremeze aims to shed light on how cassava continues to empower communities, strengthen food systems, and link traditional farming wisdom with modern innovation.